Written by Juliet Bennett Rylah

The Bee Gees made their first recordings in the late ‘50s after being discovered by radio DJ Bill Gates, having heard from racing driver Bill Goode about three talented, young songwriters performing at a Speedway in Redcliffe, Australia. Their recording career would certainly expand and evolve over the course of the next several decades, but one constant was their commitment to strong musical performances and tight harmonies. There was no fixing it in post for these prolific songwriters, who cut their teeth in a world before autotune.

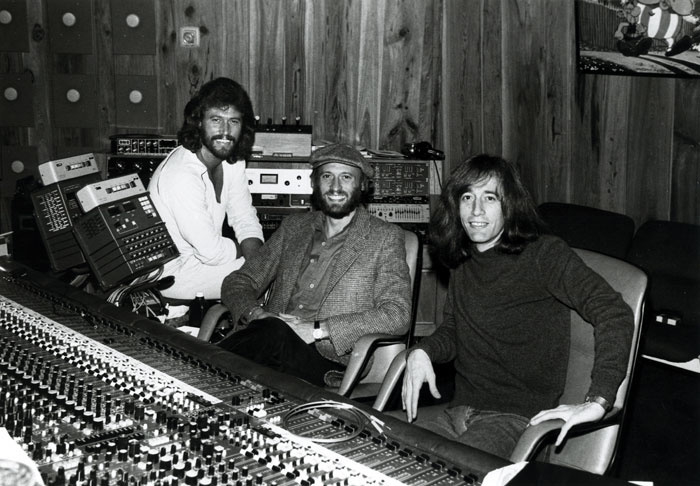

Music engineer John Merchant began working with the Bee Gees in the late ’80s, as the group was working on their 1989 album One with engineer and co-producer Brian Tench. At that time, Merchant had just graduated from the University of Miami with a degree in Music Engineering, and he’d also interned at the Gibbs’ Middle Ear Studios on South Beach. He would go on to work with the group for the next several years, over the course of which he gained a keen insight into how unique the Bee Gees’ process was. In particular, he noted how the brothers would record their harmonies not separately, but in tandem.

“The way most artists record vocal harmonies is to record one [part] at a time and get that polished,” he said. “Then, you would stack the other harmonies on top of it. [The Bee Gees] would do that sometimes, but more often, they would go out with the three of them on one mic and work out how the harmonies should be, together.”

This was not a new technique for the Gibb siblings. Michel Marie was a studio assistant at Chateau d’Herouville, the famous French country home turned studio where numerous artists—Elton John, David Bowie, and Fleetwood Mac among them—recorded hits in the ’70s and ’80s. The Bee Gees visited Chateau d’Hérouville to record “How Deep Is Your Love” and “Stayin’ Alive” for the 1977 soundtrack, Saturday Night Fever.

“When I learnt they would be three to sing, I set up three different headphones and three different mics,” Marie divulged in an interview with Sound on Sound. “They said ‘No, no!’ and asked me for a single mic, and no headphones—just a little speaker close to them. They sang together around the same mic, looking at each other. And when I heard them, I knew what ‘good singing’ meant: even on the first take, they were perfect, in tune, in the rhythm… I was not used to that from French singers!” (https://www.soundonsound.com/techniques/classic-tracks-bee-gees-stayin-alive)

Karl Richardson, an engineer who began working with The Bee Gees in the ‘70s, once said he’d tried to record them on separate mics, but it never really worked the way a single microphone did.

“The nature of their voices lent themselves to recording this way, too: Robin almost always had this cool vibrato in his delivery; Maurice had hardly any; and Barry would sometimes have vibrato and sometimes not, and when he did, it was more like tremolo,” Richardson said. “This gives you a very unique blend, which might at first seem very different from one another, but you have to remember that they’re brothers, so they have this DNA thing going.” (https://www.mixonline.com/recording/karl-richardson-375197)

Of course, recording simultaneously did present a challenge, in that all three vocal parts had become inseparably intertwined.

“If one harmony is too loud or too quiet, it’s baked in that way,” Merchant said. “There’s no way to do any of the cheats using the tools in the studio to fix intonation and balance. You can’t change any of that. And that takes real craft.”

Younger artists these days may ask Merchant to simply tune or clean up a track instead of doing another take, but the Bee Gees would do as many as 40 or 50 takes to make sure everything was perfect. It wasn’t because they rejected new technologies, Merchant said; in fact, they were quite willing to explore and invest in new developments as long is it didn’t compromise their musical integrity. They simply preferred to have things done correctly upfront and “let the musicality come from the musicians, and not from the technicians in the control room.”

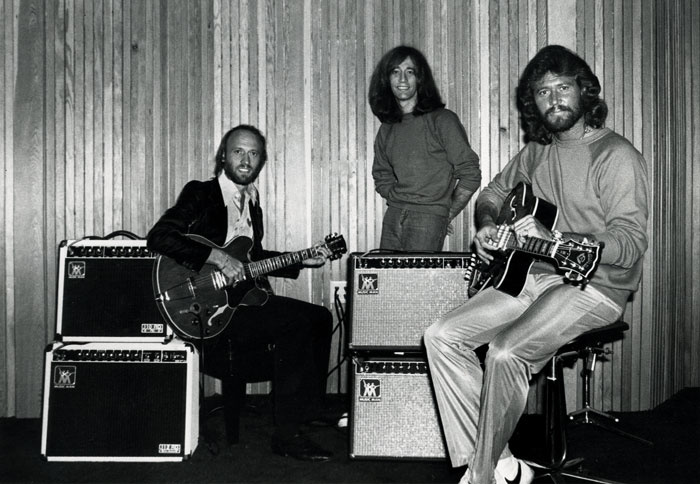

When it came to songwriting, Merchant said the Bee Gees would come in to the studio for marathon sessions where they’d set up a simple drum groove on the drum machine and toss around musical ideas for hours. Barry might play guitar while Maurice would play keyboard, and Robin would sing and come up with melodic or lyrical ideas. They’d record everything on Digital Audio Tapes (DAT), each one fitting a couple hours. Whenever a gem of an idea would occur, they’d play back the tape and mine that idea, later building upon it.

“As far as the songwriting process goes, I have never seen anyone else do it that way,” Merchant said.

The Bee Gees’ trademark harmonies were often accompanied by equally rich orchestral or brass arrangements. Though none of the brothers had ever learned read music, that never stopped them from constructing lush musical worlds. Merchant said Barry would typically sing the instrumental ideas he had, which would then be transcribed and performed by other musicians.

The group worked with multiple arrangers, including Bill Shepherd throughout the ‘60s and later producer Arif Mardin, who helped Barry find his legendary falsetto when he suggested Barry take his vocals up an octave while recording Main Course (1975).

Mardin once said, “With the Bee Gees, when we were doing the Main Course album in the mid-’70s, there was a total stream of creativity in the studio, everybody excited.”

(https://www.soundonsound.com/people/arif-mardin-producer)

Merchant said one of his favorite moments in the studio with the brothers was at the close of a long songwriting session. They had one idea they were trying to realize, but it just wasn’t working out. They decided to take a short break, and Barry suggested they return to the drawing board the next morning. However, he first mentioned he had another idea he thought might be worth pursuing.

“He started playing the intro for the song ‘Immortality,'” Merchant said. “Maurice listened, and played the first chord, and then three and a half minutes later, they wrote the song—in real time, in just one pass. I get goosebumps telling that story. It was unbelievable. Barry would change chords, and Maurice would be there immediately, like he knew where Barry was going. They locked in together in a way, both timing-wise and intonation-wise, that only someone who knows what the other person is thinking before they think it could do. So, the way you hear Celine Dion perform [“Immortality”] now is exactly how they did it [that night].”

Though it may be Merchant’s favorite anecdote, he admits the Bee Gees were not always perfectly synced. Merchant remembers numerous disagreements that could get particularly acrimonious, in the way only arguments among siblings can. Yet it was these brotherly spats that pushed each of them to their absolute best performances.

“They always knew what the other person was capable of, and so they would not rest until their brother had delivered that,” Merchant said. “It could be in terms of writing lyrics or melody or song structure or performances or arrangements. In all those things, they would challenge each other consistently.”

And Merchant always knew the arguments had come to an end when one of the brothers would suggest they put the kettle on for tea.

“And sure enough, they would walk in with a tea…and that was the indication that they were done and it was time to get back to work,” he said.